Engaged Anthropology Grant: Elena Sesma

In 2015 Dr. Elena Sesma received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “The Political Work of Memory in Collaborative Caribbean Archaeology,” supervised by Dr. Whitney Battle-Baptiste. Three years later Dr. Sesma was able to return to the field to share her results when she received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Living Memory and Changing Landscapes in Eleuthera, Bahamas: Developing a Community-Based Archive”.

The Wenner-Gren’s Engaged Anthropology Grant enabled me to return to my dissertation field site in Eleuthera, Bahamas for several weeks to continue collaboration with local research partners and participants from my dissertation research. My dissertation, titled “The Political Work of Memory in Collaborative Caribbean Archaeology” was framed around the principles of community-based, participatory research, and explored the ways in which descendants of a nineteenth century Bahamian plantation constructed and employed a collective memory around the historic and contemporary cultural landscapes of the former plantation acreage. Through a combination of archaeological and ethnographic methods, the research revealed how descendants materialized memory on a living landscape that many politicians, developers, and foreign corporations prefer to see as vacant and therefore ideal for development.

This engagement project was intended to build on the community-based nature of the dissertation project by 1) sharing research findings, copies of data, and a written community history report to participants, 2) working with collaborators and local organizations to determine possible future projects and how best to manage heritage sites, and 3) beginning to develop a local archive of island history and collective memory. During the fall of 2018, I expanded a short report of my research that I had originally composed immediately after completing my dissertation fieldwork into a much longer report that included the general history of south Eleuthera, excerpts from oral histories, a discussion of key sites of memory that might benefit from further research or conservation, and copies of historical records regarding the former plantation estate. << https://scholarworks.umass.edu/anthro_digs_reports/1/>> Additionally, I began uploading 360-degree panoramas of several significant south Eleutheran historical and cultural sites to Google Earth at the request of several former participants. << https://goo.gl/maps/MYxDMHFztpEuDWY99>>

One of the keys to community-based research, as I have learned over the process of a 5-year long collaborative project, is the need for flexibility and respect for the wishes, needs, and availability of my collaborators. This can, of course, delay the process of research or entirely reshape a well-thought out research plan, but is nonetheless an essential component of doing meaningful and productive community-based research. This engaged anthropology project, conducted in May of 2019, used the same framework, which meant that the first step was to connect with my various collaborators and partners to determine their availability and interest in proceeding with my proposal to run workshops and planning meetings around the development of a community archive. Interest was high but availability in people’s schedules was not. Instead of large-group planning meetings, I met with many of my collaborators and past participants on an individual basis to share research findings and begin discussing the potential for a locally-held and community-controlled archive. In Nassau, I met with the director of the Bahamas Antiquities, Monuments and Museum Corporation to deliver copies of the community history report I produced in the winter of 2018 as well as digital copies of data gathered during the course of my permitted dissertation research. We also discussed what the creation of a local archive might look like in terms of investment and sustainability. I also spoke with members of the descendant community in Nassau whom I had not previously been introduced to. These conversations added important nuance to my understanding of people’s relationships to the land, complicated some of my plans, but ultimately expanded the dialogue over the site’s importance and how best to care for it.

On Eleuthera, I met with representatives of local organizations and institutions, such as local librarians, non-profit directors, and the leadership of community associations. These research partners each received multiple copies of the community report and we had long discussions about how to translate this report and my dissertation into the basis for a growing community archive. I shared drafts of open access story maps that I had created based on the community report and dissertation, but together we decided to delay the publication of these maps online. Additionally, I met with almost all of my former participants who had been a part of the dissertation research, and in one case, the daughter of a participant who had died the previous year. With each person, I updated them on the status of the dissertation, shared a copy of the community history report, and in many cases, delivered hard copy transcripts of the interviews and oral histories I had done with them. As in the case of all research, it took time (sometimes years) to build rapport with some participants. In the case of southern Eleuthera, many residents have a substantial and well-justified suspicion of outsiders who show up with recording devices and paperwork. Even some of those individuals who had quickly warmed to me in the past were genuinely surprised to see me return and were taken aback when I provided copies of their interviews and a copy of the community report I wrote. It was clear then how unexpected but truly appreciated this kind of commitment and continued engagement is for communities that often feel forgotten by other institutions.

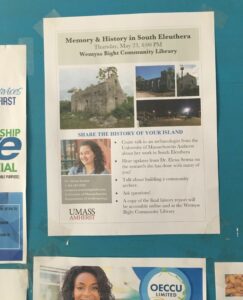

The culmination of these individual meetings and visits was a public meeting held at the Wemyss Bight Community Library. There, I shared a summary of my dissertation, some key findings outlined in the community history report, and presented several potential options for what a community archive might entail in terms of additional research and training, what form it might take, and how it might be accessed. This public meeting was both a chance for me to disseminate my research, as well as an opportunity to open the door to new questions, new participants, and ongoing dialogue between local participants and institutional collaborators.

As this project wrapped up, I reflected deeply on the process and the point of engagement in anthropology, with its many varied meanings and methods. Engagement takes on different forms, and like any good anthropologist – like any good human – we adapt. Engagement is meeting with community partners and collaborators, giving updates and talking about how to build something even bigger and better with the work we’ve already done. Engagement is meeting with officials who manage and oversee heritage resources on all the Bahamas’ 700 islands. Engagement is talking with community members who haven’t previously been involved, absorbing their frustrations at having been left out. Engagement happens amongst large groups at public meetings, where residents and researchers dialogue, fill in holes that were maybe missed in earlier research, imaging a future where this work can continue. Engagement also happens individually, in the living rooms, kitchens, front yards, and shops of those who participated. One of the most profound confirmations of this trip was acknowledging that all of these activities count as engagement, especially if the intention to share and collaborate and dialogue is there.