Engaged Anthropology Grant: Devaka Premawardhana

In 2010 while a doctoral student at Harvard University Devaka Premawardhana received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Sacrificial Exchanges: Pentecostal Conversions and Urban Migrations in Northern Mozambique,” supervised by Dr. Michael D. Jackson. In 2015 Dr. Premawardhana received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Displacement: A Seminar Series on Makhuwa Mobility”.

“Papá Baraka!”

I didn’t respond and kept on my walk.

“Oi! Papá Baraka!”

This time I turned around and saw the daughter of a good friend waving. I walked back toward her, apologizing for not knowing it was me she was calling. We exchanged greetings, asked after each other’s family, and then separated with promises for a later, longer visit.

I’m not the same person anymore, I thought to myself as I went back on my way. And I would need to get used to that.

In my year of fieldwork among a Makhuwa-speaking people of Mozambique, I was Devaka. Formally, at least. Those who knew me well called me Namanriya, the Makhuwa word for chameleon. “Vakhani vakhani ntoko namanriya,” say the Makhuwa (“slowly, slowly, like the chameleon”), an expression of admiration for the chameleon’s unique ability—not so much to change color as to walk slowly, deliberately, and at that pace to take in the margins with its laterally positioned eyes.

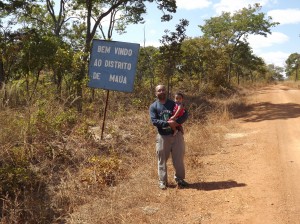

That year, I got around the district on a 50cc Lifo. It was my first time riding a motorbike, and I was riding on sandy, unpaved roads. So I never went fast. Hence, the nickname Namanriya: the chameleon who rides slowly, slowly—enough to receive greetings from those on the roadside and to reciprocate with a wave or a beep.

I was also slow in another respect. During that year of fieldwork, four years into our marriage, my wife and I were still without children. Our friends pitied us. Though we had access to more financial resources than all the village households put together, we were the poor ones. Prayers went up in the mosque and the church, and offerings were laid for ancestors—all for us to receive the blessing of fertility we had clearly been denied.

Two years later, back in the US, we received that blessing, and named him as such—Baraka. Less than a year after that, we returned to Mozambique, to bring Baraka to our friends, to present them the fruit of their ritual labor.

In so doing, my identity changed, and with it my name. No longer Devaka, and only rarely now Namanriya, I had become Papá Baraka. In this part of the world, the measure of a person, certainly the measure of one’s worth, is the quantity and quality of one’s relationships. And just as relationships change—due to births and deaths, comings and goings—so too does oneself change.

This principle of relationality is, in part, why it was so important to return to my field site with my newborn child, but also with a Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology grant and its mandate to share the results of my initial field research with the communities that made it possible.

Over a five-week period in the summer of 2016, I was able to do just that, meeting with leading scholars in the nation’s preeminent university, with research collaborators in the district where I worked, and with interlocutors in the village where I lived.

At each site, the response was immediately of appreciation and respect. Because knowledge, like identity, is grounded in relationships, people were less impressed with my ability to display an understanding of “the Makhuwa” than with my willingness to return and resume the conversations begun many years earlier.

From each of the groups, I learned something new about my research, or something in need of correcting. With each of the groups, I began thinking about how to approach my second planned project. And to each of the groups, I reflected insights I learned into Makhuwa ways of knowing and being.

Specifically, I shared my analysis of Makhuwa mobility—a propensity for movements both physical and imaginative, a predilection for making fresh starts in new places, an ease and comfort with novelty and change. One aim of the Engaged Anthropology grant is to disseminate research results in a way that offers some benefit to those among whom research was conducted. It’s my hope that, by hearing an outsider articulate the tacit, practical knowledge with which the Makhuwa by and large live, those with whom I met will be even more equipped to cope with the significant constraints on physical movement they face in the context of neoliberal land confiscations and NGO-led development efforts.

This tacit, practical knowledge—the subject of my forthcoming book—is best described as a Makhuwa disposition toward mobility and change. It’s what makes those I lived with eager to partake in resettlement schemes—whether of the developmental state or of religious institutions—but reluctant to remain settled in them. For the Makhuwa, changing is a means of enduring, becoming is a mode of being, and converting is a way of life.

By returning to my field site as the parent of a child, I learned that what’s special about the Makhuwa is not only their capacity for regular transformations, but also their readiness to mark transformations in others, even in people like me prone to seeing themselves as consistent over time, as settled rather than shifting.

No longer Namanriya, my new name was Papá Baraka. My name had changed. I had changed. Maybe, after all, it was not just my slowness that warranted the nickname of chameleon. Maybe it was my capacity—a capacity I didn’t think I had until the Makhuwa made me see it—to change and to adapt, and thereby truly to live.