Engaged Anthropology Grant: Laura Bidner

While a doctoral student at Arizona State University Laura Bidner received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant in 2005 to aid research on “Predator-Prey Interactions Between Leopards and Chacma Baboons in South Africa,” supervised by Dr. Leanne T. Nash. After successfully defending her dissertation and receiving a Post-Ph.D. Research Grant in 2011, Dr. Bidner went on to receive an Engaged Anthropology Grant in 2016 to aid engaged activities on “Clever Prey and Wary Predators: Using Monkey – Leopard Dynamics to Communicate Local Ecological Connections”.

It is late on an afternoon in June, and classes are just letting out at Ol Jogi Primary School in Laikipia, Kenya. Students mill about and laugh. One group is gathered on benches under a tree listening to a fellow student; it is a meeting of the school’s conservation club. I see familiar faces in the students and the faculty advisors of the club as I approach and sit to listen with the Princeton University student interns, who are working with the clubs this summer as well. I led activities with the club the week before on strategies baboons, vervet monkeys, and leopards use to survive around each other (i.e., to eat and avoid being eaten or attacked!) based on findings from research I conducted not far away in 2014.

Although I am not leading the activities with the club this week, I plan to ask a few follow-up questions to assess the effectiveness of last-week’s lesson at the start of the meeting. However, as soon as we sit down, I realize that the student speaking is discussing what the club did last week and what they learned from those activities! I am thrilled to find out that they had such an impact, and inspired to see the ecological interactions I have studied interpreted through new, young, Kenyan eyes.

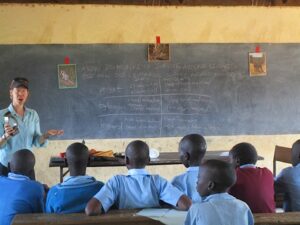

I designed my Wenner Gren Engaged Anthropology project, “Clever Prey and Wary Predators: Using Monkey – Leopard Dynamics to Communicate Local Ecological Connections,” to convey results from recent research conducted at Mpala Research Centre (MRC) – partially funded by the Wenner Gren Foundation – to the local community around Laikipia, Kenya. I was able to coordinate my activities and visits to Northern Kenya Conservation Clubs set up at local schools with Nancy and Dan Rubenstein of Princeton University, who have worked to establish these clubs over the last eight years, and two Princeton undergraduates interns working with them this summer. In addition to leading interactive lessons on the dynamic relationship between leopards and primates at ten of the twelve schools, and hands-on activities on remote monitoring techniques and footprint identification at six schools, I also assisted with set up of remote camera traps around schools, aided interns in implementing ecologically-based lessons, and helped to prepare club groups for their Community Conservation Day presentations.

Although the date of the Community Conservation Day was delayed until after my return to the US, one of the conservation clubs played the “sneak attack” game from my leopard-primate interaction lesson as their presentation to the entire community during the event.

When I arrived in Kenya in early June to embark on this project, I did not know exactly what to expect. I was very familiar with the research centre and the surrounding landscape where I had spent a year tracking groups of baboons and vervet monkeys, and stealthy individual leopards on a daily basis. As I prepared for the project in the US, I discussed how to tailor my activities to the rural Kenyan school settings with the Rubensteins via Skype and with a friend and former field assistant who had worked with the conservation clubs in the past. I also used my own experiences working with elementary through college students and international field assistants to develop engaging activities, and to design materials to distribute to the schools as part of my activities. I arrived in Kenya with handmade, laminated “gametags” for the students to identify themselves as leopards, baboons, and vervet monkeys during one planned activity, as well as a camera trap to set up during that activity, and footprint guides for a track identification and measuring activity.

Visiting the schools to meet with the faculty advisors, and discussing my plans for my initial leopard-primate activities with the Princeton interns in the first week helped me get my activities ready to go. At the research center I even found the perfect easily-transportable camera-trap stand, and an old GPS collar nearly identical to our project’s baboon GPS collars to bring to show the clubs.

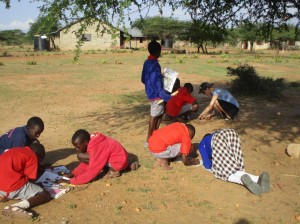

My first meeting with the conservation club at Il Motiok Primary School across the river was filled with the enthusiastic sounds of students imitating the alarm calls of vervet monkeys, squealing with delight while fleeing to trees or chasing “leopards” during the game, and laughing uproariously at seeing themselves and their classmates captured in camera trap photos viewed immediately after the game. When I planned and prepared for the project, I had been so focused on the intended conservation and educational outcomes, and on communicating these effectively to Kenyan elementary and secondary students, that I was completely caught off guard by how much unbridled fun the activities generated!

I realized that the engagement of the students in ecological activities reflected not only their thirst for knowledge about local ecology, but also their pride of place, and that these together are the keys to the future of conservation in the region in the long term. Through this project I learned so much by working with the clubs, their advisors, Mpala staff, and the crew from Princeton not only about effective communication and educational techniques in ecology and conservation, but also about Kenyan perspectives, priorities, and lifeways. I saw how sincerely everyone from Mpala staff whose children were in conservation club to the research center director, Dr. Dino Martins, valued conservation education, and I felt part of a very important, rewarding, and vital effort to help forge the path of Kenya’s ecological future.