Engaged Anthropology Grant: Sarah Osterhoudt

Sarah Osterhoudt is a Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Indiana University, Bloomington. In 2009 while a doctoral student at Yale University she received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant to aid research on “Vanilla for the Ancestors: Landscapes, Trade, and the Cultivation of Place in Madagascar,” supervised by Dr. Michael R. Dove. In 2015 Dr. Osterhoudt received an Engaged Anthropology Grant to aid engaged activities on “Engaging Landscapes: Cultural Meanings, Community Management, and Agro-Biodiversity in Madagascar Vanilla Gardens”.

For my Engaged Anthropology project, I returned to my dissertation fieldwork site: the agrarian community of Imorona, on the northeast coast of Madagascar. In this region, families have been cultivating a diversity of subsistence and market crops within hillside swidden and agroforestry systems for generations. Currently, the main market crops that growers cultivate include vanilla, cloves, and coffee. My dissertation research examined these agroforestry systems from overlapping cultural, historical, and material perspectives. It explored connections between the cultivation of land and the cultivation of self, and asked how the work of farming simultaneously emerges as the work of history.

In addition to my ethnographic research methodologies, including working alongside vanilla farmers and recording oral histories of landuse and trade in the region, my work also incorporated methodologies in economic botany. With the assistance of seven local farmers and two local research assistants, I inventoried a sample of Imorona vanilla gardens. Working in measured plots, we recorded the local names, the various uses, and the DBH measurements of the trees found in Imorona vanilla gardens. We collected and dried specimens of each of the tree species found in our study, which I identified with the assistance of botanists at the herbarium at the University of Antananarivo.

The results from this economic botany work were quite striking: in a small sample of seven vanilla fields, we recorded nearly 100 species of trees, nearly a third of which were native to the humid forest ecosystems of Madagascar. Additionally, ecological measurements of the agroforestry fields, including diversity index values and rank abundance curves, showed that these managed forests closely matched the dynamics of “natural” and protected forests in Madagascar. From a cultural perspective, farmers identified a use for 100% of the trees recorded in their fields. Interestingly, while about 75% of these uses related directly to people (for example, for use for food, income, ceremonies or building materials) the other 25% of the trees were primarily noted for their purpose in fostering healthy ecosystem relationships (for example, providing habitat or food for bird and animal species).

Such notable results, I believe, are powerful tools for Imorona farmers as they continue to advocate for their land rights and autonomy. Within Madagascar, as within much of the tropics, dominant conservation narratives often portray smallholder farmers –especially swidden farmers — as destructive environmental actors who fundamentally threaten the health and diversity of rainforest ecosystems. As a result of such conceptions, agricultural land has been taken from Malagasy communities in order to be placed within protected areas. In contrast to such environmental narratives, however, the results of my collaborative research tell a much different story about smallholder Malagasy farmers: one of careful land stewardship based upon extensive environmental knowledge, whereby agricultural practices promote the ecological diversity and integrity of tropical landscapes.

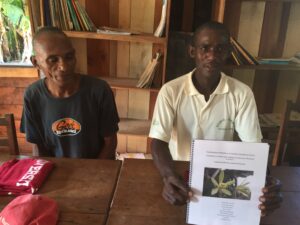

With these points in mind, I traveled back to my field site for my Engaged Anthropology project. The first objective of my project was to share with the community – especially my research assistants –the economic botany research results, translated into Malagasy. In a small ceremony held at the Imorona community library, I presented participating farmers with printed copy and a digital copy of this booklet and thanked them for their work on the project. A copy of the booklet will be housed at the library and will be available for all interested people to read. After the ceremony, I discussed the results of the botanical and ethnographic studies in detail with interested farmers. We went over together what exactly the results indicated and how the community could meaningfully use the data when speaking with government agencies and environmental groups.

I also conducted a “walking workshop” with several vanilla farmers, visiting their fields and discussing the challenges and questions that they were currently encountering. In the course of such field visits, farmers raised some concerns, including the increase in a root disease spreading across vanilla vines, the changing patterns of flowering times for key economic crops, and the increasing incidence of immature vanilla flowers dropping to the ground before they opened. Together, we discussed ways that further collaborative research in anthropology and economic botany could help address these challenges.

Finally, I spoke with other organizations that I felt had a potential interest in the results of the research. Within the Imorona region, I met with local farmer organizations, Peace Corps volunteers, vanilla exporters, and government extension officials. In Antananarivo, the capital city of Madagascar, I spoke with representatives from organizations including the University of Antananarivo, the World Bank, Peace Corps, the World Wildlife Fund, Fair Trade organizations, and the United Nations.

Overall, the experience of my Engaged Anthropology grant provided me the resources to have the incredibly valuable opportunity to do what we all aspire to do as anthropologists: say an in-person thank you to the people who inspired and empowered our work, and to give back in some way. Reconfirming such personal connections, in turn, speaks to another level of anthropological engagement: the continuation of the personal engagements we develop in the places where we work, as we move forward in our lives as scholars, and as friends.