Engaged Anthropology Grant: Joshua Samuels and “‘Patrimonio S. Pietro’: The Heritage of Agricultural Reform in Western Sicily”

Joshua Samuels earned his Ph.D. from Stanford University and received a Dissertation Fieldwork Grant in 2010 to aid research on ‘Reclamation: The Archaeology of Agricultural Reform in Fascist Sicily,’ supervised by Dr. Lynn Meskell. This year, he was awarded the Engaged Anthropology Grant to enable him to return to his field site in Western Sicily, where he explored how Sicilian farmers negotiated Fascist land reforms and building programs of the 1930s and early 1940s, to share his research results with the community that hosted him.

I first visited Borgo Bonsignore in 2006 when I began my dissertation research investigating land reform in Sicily under Fascism. In Italian “borgo” literally means village, but under Fascism the term was used to describe service centers, built from scratch, that were designed to serve the civic and social needs of farmers being resettled in newly built farmhouses in the countryside. In the 1930s and early 1940s, borghi and farmhouses were constructed all over Italy as part of a Fascist ruralization campaign that aimed to increase agricultural production and, in the process, encourage fecundity and allegiance to the Fascist regime.

I first visited Borgo Bonsignore in 2006 when I began my dissertation research investigating land reform in Sicily under Fascism. In Italian “borgo” literally means village, but under Fascism the term was used to describe service centers, built from scratch, that were designed to serve the civic and social needs of farmers being resettled in newly built farmhouses in the countryside. In the 1930s and early 1940s, borghi and farmhouses were constructed all over Italy as part of a Fascist ruralization campaign that aimed to increase agricultural production and, in the process, encourage fecundity and allegiance to the Fascist regime.

My dissertation research had two goals: to reconstruct the agricultural landscapes of borghi and farmhouses that developed under Fascism, and to understand the process through which these buildings and landscapes have today been re-used and re-contextualized as heritage resources. I pursued the first goal in a 20 square kilometer area around Borgo Fazio, an abandoned village in middle of Sicily’s northwestern corner. For my second goal I turned to Borgo Bonsignore, located on Sicily’s southwestern coast, where I spent the summer of 2010 conducting ethnographic research. After several waves of abandonment and re-use, the borgo is now a popular seasonal destination for families from the nearby city of Ribera, who have either built second homes there or occupied the empty municipal buildings. Families generally arrive in June and spend several months enjoying the beach and nature preserve located just down the road. They also avail themselves of a series of outdoor events that take place in the main piazza, organized since 1997 by Ribera’s tourism board and the Associazione Pro-Borgo.

With the support of the Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology Grant, I returned to Borgo Bonsignore in August of 2013 to organize a public heritage event in the main piazza. My goal was to appropriately contextualize the borgo’s existence within the Fascist agricultural, demographic and colonial policies which engendered its construction, but without denying its subsequent development and the affectionate feelings its seasonal residents have for it today.

With the support of the Wenner-Gren Engaged Anthropology Grant, I returned to Borgo Bonsignore in August of 2013 to organize a public heritage event in the main piazza. My goal was to appropriately contextualize the borgo’s existence within the Fascist agricultural, demographic and colonial policies which engendered its construction, but without denying its subsequent development and the affectionate feelings its seasonal residents have for it today.

I had originally intended to stage the event at the end of July, but the president of the Associazione Pro-Borgo thought it would be most appropriate to include it as part of the local Saint’s Day celebrations held during the third weekend of August. In collaboration with a local historian from Ribera and a university student whose family summers at the borgo, I prepared a series of poster exhibits providing basic contextual information relating to pre-20th century Sicilian agriculture, Fascist colonial-agricultural policy, and Borgo Bonsignore’s specific development. In every poster I attempted to balance an appreciation for what was achieved in the area with a recognition of its underlying totalitarian logic. The posters were affixed to light poles around the central piazza, allowing participants to browse them casually without interrupting the weekend’s religious events.

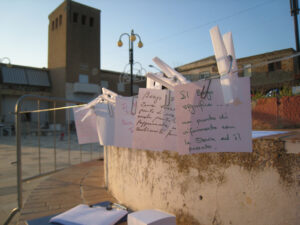

I designed the event to be interactive and collaborative. Many of the posters encouraged readers to add notes of their own, and two weeks prior to the event I posted fliers asking residents if they would be willing to share photographs, personal objects, stories, or ideas. We also strung a clothes line near the center of the piazza and asked participants to reflect on what the Borgo meant to them; they wrote their responses on notecards that were then affixed to the line. About half of the cards were contributed by children, allowing them to engage the material in a creative and meaningful manner. The following are translation from among the dozens of responses posted:

I designed the event to be interactive and collaborative. Many of the posters encouraged readers to add notes of their own, and two weeks prior to the event I posted fliers asking residents if they would be willing to share photographs, personal objects, stories, or ideas. We also strung a clothes line near the center of the piazza and asked participants to reflect on what the Borgo meant to them; they wrote their responses on notecards that were then affixed to the line. About half of the cards were contributed by children, allowing them to engage the material in a creative and meaningful manner. The following are translation from among the dozens of responses posted:

- “The borgo means love and happiness”

- “Borgo means getting to know new friends”

- “Borgo Bonsignore is the place where I spent my happy and lighthearted adolescence. It preserves my soul!”

- “Borgo means history, life, and knowledge”

- “Borgo means a return to roots, to families, to UNITY”

- “The borgo means…past and future”

- “The borgo means…a point of reference with history and the past”

- “For me it means a desire to eat gelatos and pizzas”

- “Borgo means peace, serenity, love and serenity. I love you Borgo”

The event began on Saturday, August 24th and continued until the following Monday. The piazza was full during the evenings because of the Saints’ Day celebrations, allowing me to easily mingle with people viewing the exhibits. We discussed the research I had carried out, and asked each other questions about the materials presented. Most of the participants were seasonal residents, but a handful of the people with whom I spoke were passing tourists with no prior knowledge of the borgo’s unusual history.

I had hoped to display the event’s posters and other materials in a permanent exhibit housed in one of several spaces that were empty or underused when I originally conducted my fieldwork. Two obstacles conspired against this plan. First, all of the available spaces had become occupied in the intervening years; second, a sudden rainstorm on the evening of August 27th destroyed all the posters. However, the event generated a great deal of enthusiasm, and plans are already underway to stage another version next year. Since leaving Sicily I have been receiving a steady stream of old photographs and stories, and look forward to incorporating them into next summer’s event.

I had hoped to display the event’s posters and other materials in a permanent exhibit housed in one of several spaces that were empty or underused when I originally conducted my fieldwork. Two obstacles conspired against this plan. First, all of the available spaces had become occupied in the intervening years; second, a sudden rainstorm on the evening of August 27th destroyed all the posters. However, the event generated a great deal of enthusiasm, and plans are already underway to stage another version next year. Since leaving Sicily I have been receiving a steady stream of old photographs and stories, and look forward to incorporating them into next summer’s event.

And what does the borgo mean to me? I will always find Borgo Bonsignore somehwhat unsettling, but it nonetheless serves as an example of how a difficult heritage can be re-qualified and used productively in the present.