Interview: Oli Pryce and the Iron Kuay

Oli Pryce is Junior Research Fellow at St. Hugh’s College, University of Oxford. In 2009 he received a Post-Ph.D. Research Grant to aid research on ‘The ‘Iron Kuay’: Ethnoarchaeological Investigations of Technological Continuity and Socio-Economic Interaction with the Angkorian Empire’ In association with Dr. Mitch Hendrickson (University of Illinois-Chicago) and Dr. Stéphanie Léroy (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique). We asked Dr. Pryce a few questions about metallurgical archaeology and his research with the Cambodian Kuay.

How did you come to study Kuay metallurgy? In a nutshell, why do you find it interesting?

Prior to the Kuay project I had always worked in prehistoric archaeology: first in the Mediterranean and then in Southeast Asia for my Ph.D. from 2005. It was during my doctoral studies of predominantly 1st millennium BC copper production in central Thailand that I became aware of colleagues working around the world on the interpretation of social context of metal production through variation in the resulting slag chemistry and morphology. This may sound a little far-fetched but in many instances, and as was certainly the case for my Ph.D., slag is the most abundant archaeological material available on production sites, and thus we must attempt to squeeze the maximum possible cultural information from this outwardly unyielding waste material. Previous such case studies had naturally focused on much more intensively researched areas in Africa and Europe, but whilst these were of course very useful and made sophisticated use of rich datasets, I hoped to develop a more regionally-based methodology for cross-cultural ethnoarchaeological analogies. Southeast Asia is, or certainly was, extremely rich in metallurgical traditions but previous surveys of the available ethnographic and historical data by Bennett Bronson at the Chicago Field Museum indicated that the Kuay iron smelting tradition of north-central Cambodia, which ended only in around 1950, was the most promising.

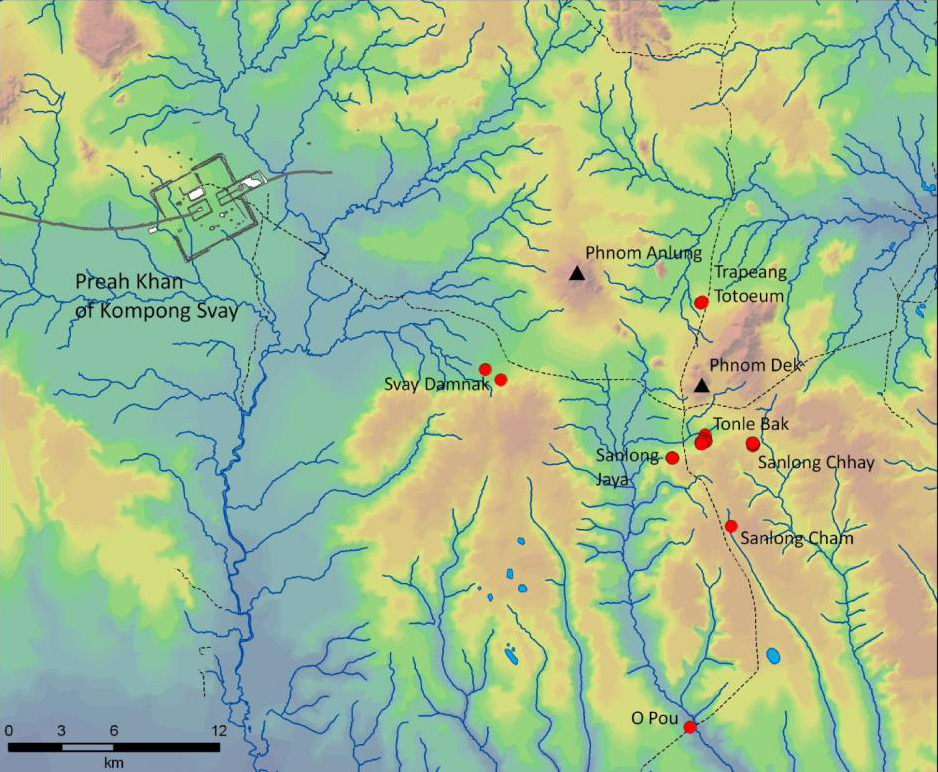

It was at this juncture that good luck brought about the meeting of my former Ph.D. supervisor, Prof. Vincent C. Pigott (University of Pennsylvania Museum) with Dr. Mitch Hendrickson (University of Illinois-Chicago), one of the only Angkorian period (9th to 15th c. AD) archaeologists to work outside of the Angkor complex in Cambodia. Dr. Hendrickson’s « Industries of Angkor Project » or « INDAP » was established explicitly to investigate the economic, political, and social factors involved in the production and supply of raw and finished materials from Angkor’s hinterlands to the imperial capital. Iron and steel were of course essential materials for agriculture, building, and warfare, and the proposed major centre of production at the Angkorian complex of Preah Khan or Kompong Svay was situated 100km east of Angkor itself, but intriguing only 30km west from Cambodia’s largest iron oxide source, Phnom Dek or Iron Mountain, and the historic homeland of the Kuay ethnic minority. Given the convergence of our interests, Dr. Hendrickson and I set about investigating the hypothesis that the well-recorded 19th and 20th c. AD Kuay iron smelters around Phnom Dek were in fact the descendants of the Angkorian period iron smelters at Preah Khan of Kompong Svay. As it happens, we have so far established strong technological continuity – not stasis but gradual changes – going back to the 8th c. AD and thus pre-dating Angkorian state formation.

Your project intended to walk the line between cultural anthropology and archaeology, incorporating assemblage analysis within a more traditional archaeological framework alongside oral histories informed by the ethnographic tradition. What were the challenges of implementing such a research program, and how did you adapt to those challenges?

Yes, the initial proposal did lay out a hybridised methodology, which had appeared to us as most suitable during reconnaissance work in early 2009 when we met several witnesses to Kuay iron smelting operations. However, once we arrived for our main field season around Phnom Dek it became apparent that we were late, much too late, for this type of work. One of our 2009 informants had regrettably died that year, and though we recorded an instance of a local lady who had been permitted to deliver food to the smelters as a prepubescent girl (thus respecting fertility taboos), the Kuay elders from numerous local villages who kindly agreed to be interviewed all transpired to have been too young to have actually participated in pre-1950 smelting activities. The last Kuay smelters, who would have been fit men to maintain an all-day relay for the bellows according to historical records, were not interviewed during the period when Cambodia was too politically troubled for foreign researchers. Particularly emblematic of the fragility of highly skilled technical traditions, the Kuay attempted to revive smelting activities in the mid/late seventies to comply with Khmer Rouge policies on self-sufficiency, but failed as all the smelting masters (chhay), the porters of at least 1200 years of metallurgical tradition, had died in the intervening quarter century. In response to this we decided to employ a solidly archaeological/archaeological science approach to reconstructing Kuay metallurgy, but continued to record the oral histories for the information they may reveal later and also because even the Kuay iron smithing tradition appears to be in terminal decline.

How did other anthropological studies of metallurgy in other regions of the world influence your project?

Massively. Research into traditional and ancient metallurgy has been carried out extensively from South America, to Europe, to South Asia, but where the deep-time perspective has been most intensively reconciled is in Africa with literally hundreds of case studies involving informant interview, experimental reconstructions, and archaeological excavations. Though I am obviously not expert in all these regions, through my general training in ancient technologies at the University of Sheffield and at University College London I was able to bring to the Kuay study an awareness firstly of the key thermodynamic principles that must be obeyed for iron metal to be produced, but also the simply staggering variety with which these challenges have been overcome in very different cultural contexts through time and space. The key insight for our interests was that as a skilled technology with numerous possible technical solutions, chronologically and spatially persistent traits in iron production may indicate the close and cooperative teaching environments to be expected of ‘social continuity’ at some level – i.e. we wouldn’t want to define ‘a people’ based purely upon their metallurgical tradition but we would expect technological changes over time consistent with innovations in response to cultural, economic, and physical environments for which we can investigate corroborating evidence.

What can study of the interactions between the iron smelters of the Kuay and the Angkorian Khmer teach us about imperial power? About modern-day Cambodia?

Although work is very much ongoing, what is fascinating about the Kuay study is that following Dr. Hendrickson’s work we can see that the architectural expressions of Angkorian state infrastructure (roads and bridges) do not extend beyond the Preah Khan of Kompong Svay complex in to the forested territory surrounding Phnom Dek: Preah Khan seems to mark a frontier of the Khmer Empire. My own iron smelting reconstructions, with the help of Dr. Michael Charlton, do not seem to suggest any substantial technological discontinuity between production sites at Preah Khan and those around Phnom Dek, but the work of Dr. Stéphanie Leroy certainly indicates that two different sources of iron oxide were used. At this stage then we might propose that Khmer workers at Preah Khan imitated Kuay practice with local materials, or that Kuay workers were active in a very much state-oriented production there; either as paid, indentured, or slave labour. What does seem more clear though is that the hundreds of smelting sites of various sizes all around Phnom Dek represent Kuay family or community-level production; with the resulting iron supply reaching Angkor c. 130km east through either tribute, taxation, or free market operations. This provisionally shows us that although the Angkorian Empire is celebrated for having extended over much of mainland Southeast Asia between the 9th and 15th c. AD, the precise configuration and penetration of imperial power probably varied quite significantly by region and period. At a more general level we might conclude that no imperial territory maybe under total control all of the time, but that once stabilised economic activity involving established or mobile populations is a prerequisite for long-term success. In terms of modern countries like Cambodia or its neighbours, the characteristics of national identity (culture, history, and language) are usually drawn largely from those of lowland governing majorities but through the careful coordination of archaeological, ethnological, and historical records we may be able to demonstrate that geographically marginalised minority groups have long participated in and contributed to the development of nation states.

What are some next steps for this research? What do you see in the future?

At present we are broadly happy with our research questions and methodology but recognise the need to ‘thicken’ the dataset with higher density chronological and spatial coverage of Kuay production and settlement sites, and to increase the resolution of technological reconstructions by ever more careful excavation techniques and bringing in other expert opinion. The project is also amenable to geographic expansion: iron smelting material excavated by the Thai/Khmer Living Angkor Road Project are currently being studied by Mr. Pira Venunan, a Thai Ph.D. student at University College London, some of whose sites are located in linguistically ‘Kuay’ areas in northeast Thailand. Kuay sites are also known or suspected all the way up to and beyond the southern Lao border, so there is plenty of work to do! Although decades of research lie before us we share the ambition of being able to contribute towards a detailed long-term understanding of which social groups in which areas were providing which goods and services to each other and thus how their combined economic and political interaction contributed to the rich history of Southeast Asia.

Are you a current or past Wenner-Gren grantee and are interested in being interviewed for the blog? Contact Daniel Salas (dsalas@wennergren.org) for more information.