Interview with Elise Kramer on “Mutual Minorityhood”

Elise Kramer is a Ph.D. student in Anthropology at the University of Chicago. She received a Wenner-Gren Foundation grant in May 2010 to assist research on ‘Mutual Minorityhood: The Rhetoric of Victimhood in the American Free Speech/Political Correctness Debate,’ supervised by Dr. Susan Gal. Below is a short interview we conducted to dig deeper into Kramer’s interest in the complex dynamics of victimhood in American public life.

Elise Kramer is a Ph.D. student in Anthropology at the University of Chicago. She received a Wenner-Gren Foundation grant in May 2010 to assist research on ‘Mutual Minorityhood: The Rhetoric of Victimhood in the American Free Speech/Political Correctness Debate,’ supervised by Dr. Susan Gal. Below is a short interview we conducted to dig deeper into Kramer’s interest in the complex dynamics of victimhood in American public life.

What first drew you to study the ACLU in an anthropological capacity?

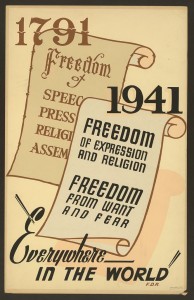

It was definitely a case of my topic driving my field choice rather than the other way around. Starting from my observations of mutual minorityhood (see below), I wanted to study the ways that the concept of freedom of speech is invoked in political debates in the U.S., with an eye toward the ways in which accusations of censorship stand in for more fraught and fundamental disagreements over who truly has power in American society. I had noticed that many political disputes in the U.S. seemed to boil down to competing claims of being silenced—and this raised some interesting questions for me about a) why this was an intelligible and persuasive direction to take a political argument, and b) what this focus on censorship can tell us about the nature of the modern American political field.

The ACLU’s place in the political landscape crystallizes many of the seeming paradoxes at the center of my project. In theory, the organization’s guiding principle is the defense of the Bill of Rights, which is a cause one would expect to gather almost universal support among Americans (especially when it comes to freedom of speech). But in practice the ACLU is a highly contentious organization: for some it is the embodiment of unbiased justice for the underdog; for others, an anti-religious stalwart advancing a hegemonic liberal agenda. Studying the process by which which the ACLU’s choices of which issues to take up get refracted and reframed both within and without the organization seemed like a good place to start in tackling such broad and omnipresent questions.

Could you briefly explain what is meant by “mutual minorityhood”? How does it manifest itself in American public life?

By “mutual minorityhood” I mean the phenomenon that so often occurs in American politics where each side of a debate perceives itself as a victimized minority and its opponent as a hegemonic majority. There are examples of this pretty much everywhere you look: the immigration debate, the gay marriage debate, the debate between feminists and men’s rights activists, etc. In each of these instances, you will find people on each side of the debate claiming that theirs is the beleaguered—even iconoclastic—underdog fighting a burgeoning superpower.

The phenomenon is worth studying for at least a couple of reasons. First, that the mantle of “true” victimhood would be so appealing and highly-contested raises important questions about American ideologies of power, agency, and dominance. Second, I think it’s vital to have an anthropology of power that is cognizant of actors’ self-reflexive beliefs about their place in the sociopolitical landscape; whatever “real” power dynamics may exist, the ones that people perceive and act in relation to are just as analytically significant when trying to understand the cultural processes in play.

Many Americans would hold that Freedom of Speech is a relatively straightforward concept. You propose that the understanding of that concept is shot through with a number of “folk beliefs”. How does your work in Linguistic Anthropology draw this out?

Though freedom of speech may seem like an ahistorical and objective concept, if one looks at even the short history of first amendment doctrine in the United States, one will find that “freedom of speech” has meant very different things at different moments. The free speech clause of the first amendment was originally interpreted as protecting primarily the press and even then only in a “no prior restraint” capacity (it was considered perfectly constitutional to punish someone for printing something so long as you didn’t actively prevent him or her from printing it in the first place). This now seems unbelievably savage to most Americans, who generally see free speech as an unfettered individual right. (See Stephen Feldman’s Free Expression and Democracy in America for an excellent history of the evolving American understanding of freedom of speech.)

As a linguistic anthropologist, I am interested in what language ideologies (taken-for-granted beliefs and assumptions about how language works and how people use it) underlie the many ways of thinking about and talking about “freedom of speech” in the U.S. Different rationales for why free speech is important (e.g. the “marketplace of ideas,” self-governance, the self-actualizing nature of civic participation) highlight different “functions” of language, privileging some categories of language and leaving others unprotected. And because language ideologies often link certain “types” of people to certain “types” of language, it is difficult to talk about freedom of speech without implicitly making judgments about who has the right or privilege to speak. Using a linguistic anthropological approach that is sensitive to the hidden assumptions undergirding debates about censorship specifically and about “voice” and power more generally, I hope to render well-worn political stalemates in a new light and maybe even create new possibilities for understanding in an especially fractious climate.

Are you a current or past grantee and want to be featured in a mini-interview on our blog? Contact Daniel (dsalas@wennergren.org) to find out more.